“The waiting is the hardest part.”

“The waiting is the hardest part.”

–Tom Petty

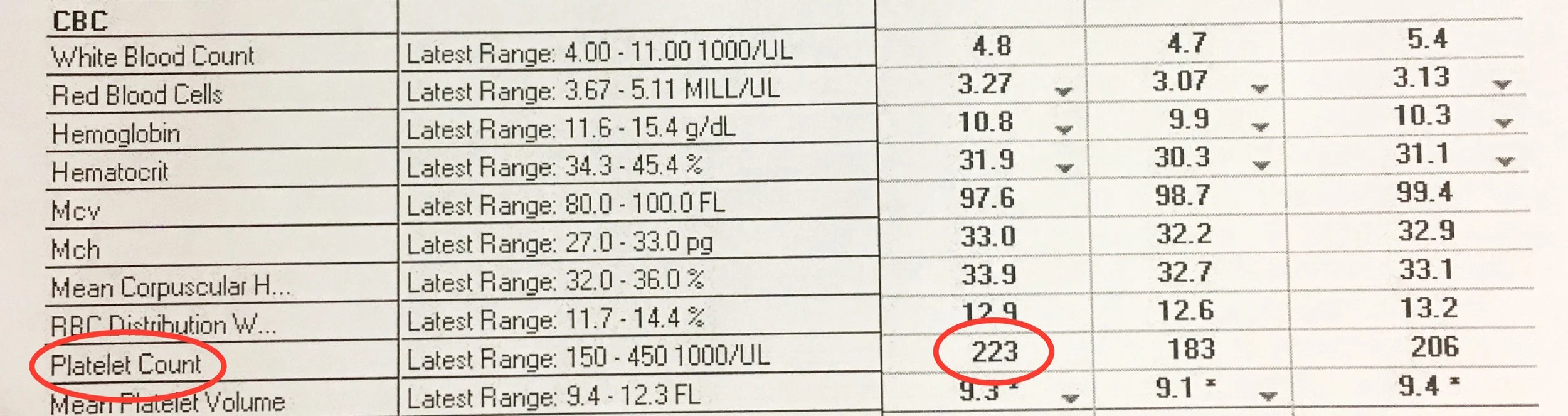

My complete blood count (CBC) was in December. I get the test every three months, and had a big drop in my numbers early last fall. Over the summer, we’d been to Tuscany, Barcelona, a ranch in Montana and the wilds of suburban Ohio, and travel takes a toll on me. Besides, running around with a ten-year-old boy is tough on any mom, let alone an old one like me with a rare bone marrow failure disorder. My fear is loss of platelets - a trend downward headed toward bruises, exhaustion, and please God no – another hospital stay – or worse. But this time, I had 232,000 platelets and a red blood cell count of 10.8 – my highest numbers since diagnosis - and pretty much normal levels.

“I’ve been feeling pretty good.” I told my family over a celebratory sushi dinner. “I was nervous, but not worried.”

“Same thing.” my eleven-year-old son Theo shot back.

“Not really.” I replied. “Nervous is unsettled, unsure. Worried is being afraid of the outcome. Fear of the future.”

“Same thing.” he said, sticking to his guns.

I looked it up on my phone and sure enough, many a crossover definition. Damn these little smarties.

Some Aplastic Anemia patients are treated with Anti-Thymocyte Globulin. The Wiki definition of ATG states that it is “an infusion of horse or rabbit-derived antibodies against human T cells, which is used in the prevention and treatment of acute rejection in organ transplantation as well as therapy of Aplastic Anemia.” ATG works in 7 out of 10 patients, those that for various reasons are not candidates for a bone marrow transplant, the cure for AA. I received ATG in the fall of 2015, as I had only 2000 platelets and was close to bleeding out. No time to find a marrow match.

Think of me like a Mac computer, getting rebooted after a crash. The ATG brought me down to zero, tricking my body into thinking it had a bone marrow transplant. We waited with fingers crossed to see if I would respond and begin to make blood cells on my own, as if the Apple logo had popped up, and we were hoping for that white line to start rebuilding my cellular desktop.

We waited for “The Uptick”.

Two years ago, just six weeks after my five-day, in-patient, chemo-like treatment in the cancer ward, I had mine. No fanfare nor confetti. Platelets and red blood cells humbly started to grow on their own. I stopped living off transfusions of someone else’s blood received at the UCLA cancer center every other day, which had started to feel like the part time job of keeping myself alive. It was a miracle, as patients generally wait 3-6 months for cell growth.

You’d think after that initial uptick, the official sign that the ATG has worked, I wouldn’t get nervous before my CBC. Three months ago, my blood work had shown a drop of 30,000 platelets. I was devastated, having been the poster child for success with this type of treatment.

“What are you worried about? 183,000 is still well in normal range!” exclaimed Ron Paquette, or ‘The Guy’ – the guy that saved my life – my hematologist.

“You aren’t the patient. You’re so...Rational,” I countered.

“Maybe you should meditate,” my wife had to remind me in those early days, especially before my diagnosis, when I was covered in bruises and we knew something was terribly wrong. When you’re wishing for leukemia, you know you’re in a pickle.

So I sat. I meditated in examination rooms, waiting areas, transfusion chairs and hospital beds. I meditated by my friends’ pool and in Coma Corner, the special spot on my couch at home where I sleep the best. I just closed my eyes, and I breathed. I gave my mind a mini vacation from thinking. I still do.

I’ve gotten pretty good at living in the not knowing. I’ve learned to manage the fear. I sit and breath, and remember that all we really have is this breath. This breath. The next one. The one after that. It’s true - we never really know what’s coming, so why waste time fretting?

When Sara, Dr. Paquette’s nurse, read the results of my CBC last month, I did the Snoopy dance. Now I can forget about it until I find a wayward bruise, sneeze one time too many, or in three months when it's time for my next blood test and I’ll be nervous - but hopefully not worried.